Overlay Takeouts

By Florian Marienfeld (, ), Jochen Hänsel, Jochen Pfeiffer (, ) and Tine Oymann.

Takeouts or stealing patterns have been around for a long time already and are still very popular. Yet, working with even newly created takeout patterns feels like doing the same fourcount based patterns over and over again. We propose to break this stagnation by leveraging Prechac based patterns and make both passers and manipulators do passing actions that combine the fun of takeout- and Prechac-patterns.

Discuss at juggling.tv, acebook.

Introduction

In juggling the term “takeouts” typically refers to one or more jugglers doing a pattern while an extra juggler (often referred to as manipulator) “stealing” a prop out of the pattern and replacing it with another. This style has been known at least as far back as 1995 (see Charlie Dancey’s Compendium of Club Juggling and Walter N. Long’s Wally Walk). These patterns were increasingly popular and were soon also performed on stage (Take That Out performance starting in 2000 and its sequel Get The Shoe starting in 2002). Takeout enthusiasts have generated an enormous variety of complicated and beautiful patterns, many of them collected in Aidan Burns’ famous ‘How to steal from your friends’. An example applies this style in a very focused manner is Bruno’s Ace – Bruno’s Nightmare with two rotating manipulators.

However, all these variations boil down to three club cascades with synchronous 4-count passes manipulated with substitutions, intercepts and carries, as Warren’s article on Scrambled Passing Patterns explains, some 2-, 3- and 5-counts being the exception.

Another line of developing new interactions between jugglers is based on Christophe Prechac’s article on Symmetric Passing Patterns. He essentially extended the generative power of siteswaps to the passing world. This technique has been extensively investigated by the Gandinis, leading to Sean’s well known Prechac explanation and ultimately to the well known Social Siteswaps DVD. A practical tool to generate these patterns is PrechacThis. A denser compilation of takeout-inspired Prechac Siteswap patterns is the Under Prechac routine.

Yet, that branch is focused on symmetrical patterns, i.e. every juggler is doing the same pattern. In takeouts on the other hand, a base pattern is manipulated by someone who does something to the pattern.

Our idea was to join these two lines of development: the running manipulators and unrestricted patterns. More specifically, instead of limiting the interactions to only three different ones between manipulator and passers and mostly four-count based passing, we looked at various periods for a pattern (3, 4, 5, 6) with no limitation on the number of passes and no limitations on selfs and passes (0, 1, 2, 3, 4 as selfs and 1p, 1.5p, 2p, 2.5p, 3p, 3.5p, 4p, 4.5p as passes).

The basic idea we explored is: Choose a Prechac passing pattern and overlay it with a custom made manipulation siteswap (another Prechac pattern).

In the next section we introduce such a new pattern as an example to give a quick start to the broad idea. This is followed by a deeper and more general explanation of the approach. By exploring a further example, with more of the intended features, we elaborate on advantages that we found in this new technique.

Motivating Example: Delightful

One well established takeout pattern is the so called roundabout: a 6 club 4-count with a manipulator substituting passes and selves, where the manipulator swaps roles with a passer who will then become the new manipulator and so on.

Based on this pattern we want to introduce our idea with a simple proof of concept. We chose to start out with a low amount of clubs (5 for the passers, 1 for the manipulator) and a not so demanding pattern 5 clubs, period 4. We decided for 3p 3 1 3.

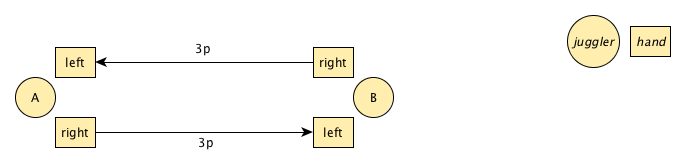

The passers face each other and all passes are straight, so for passers A and B the pattern looks like this:

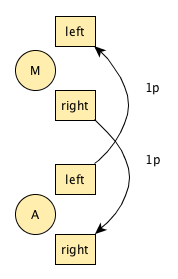

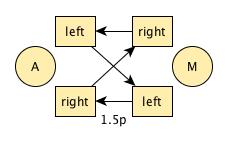

We now add a manipulation pattern by first coming up with a solo siteswap (3 1 3 1) and then overlaying it to one of the passers by using Prechac’s theory. This will allow the passer and the manipulator to share the 3 and transform it into a 1p, resulting in 3 1 1p 1 between passer A and manipulator M. A and M stand side by side and the 1p is going inside to outside:

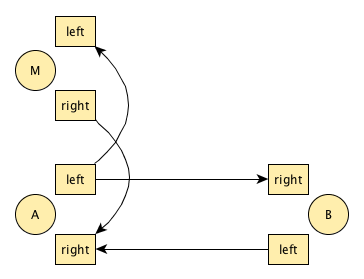

If we include passer B into the picture again, we see that B continues with the passing pattern and A does both, the passing pattern and the manipulation pattern at the same time:

Finally we have three different roles:

- A: 3p 3 1 1p

- B: 1 3 3p 3

- M: 1 1p 1 3

Note that both B and M are staggered in reference to A, i.e. they are throw their passes to A half a period shifted from A.

A good way to get the pattern started is to let A have two clubs in the right hand and start with the right hand into 3p 3 1 1p, zipping the 1 into a wrong end catch. B and M can react intuitively.

Discuss at juggling.tv.

The runaround part (swapping roles) is almost as easily achieved as in the classic roundabout. Passer A gives her last club to manipulator M and walks over with one club to the other passer B, leaving M as the new passer and becoming the new manipulator. Passer B has to do a short pattern change, i.e. 3p 3 1 3 3p 3 3p 3, where the two-count style clubs are thrown to first the former passing partner A and then to the new passing partner M.

The General Principle

With this simple example in mind we will have a look at a set of more generic activities (algorithm), that will always generate valid patterns:

- Start with a two juggler symmetric passing pattern with a length of period, that contains at least one self where \(self >= 1 + \frac{period}{2} \).

- Take a solo pattern of length period containing self. Transform that self into the \(manipulation\_pass = self - \frac{period}{2} \).

- Let the manipulator M do the pattern from step 2, exchanging the manipulation_pass with A; let passer B juggle the pattern from step 1; and let passer A do the pattern from step 1 with B, except, instead of self, the manipulation_pass exchanged with M. B and M are juggling their patterns with the starting points staggered appropriately from A.

- Optionally, walk around, swapping roles, e.g.

- M becomes a B passer

- A runs to the other side and becomes a manipulator

- B then starts in role A.

The total amount of clubs \(n_{total}\) equals the amount of clubs of the passing part \(n_{passing}\) plus the clubs of the solo version of the manipulation pattern \(n_{solo}\) minus 1, since the manipulator adds \(n_{solo}\) clubs but shares one club with a passer:

\( n_{total} = n_{passing} + n_{solo} - 1 \)

In theory, this always works. In practice, there are two things that one should bear in mind to avoid an unnecessarily hard pattern: a) Don’t catch passes under 4s as this will often lead to timing issues; b) if you have a 1p or 1.5p make sure you can resolve the resulting wrong-end catch, by enforcing a 1 or 2 self on that 1.5p-club immediately before or after the 1.5p. You will find this tweak in the following example.

Fully Fledged Example: Mission Impossible

Now that we have established the general approach, consider a pattern that incorporates more of the elements that we aimed for in the first place:

- It should be left-right-handed, hence with an odd period. We’ll use period 5.

- There should be a 1 1.5p, i.e. a “smash-in” preceded by a grip-correcting 1.

- Not too difficult for the passers, i.e. 5 clubs, just one pass and a low one at that.

This is what PrechacThis offered us.

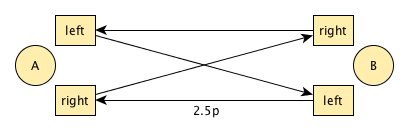

Our first attempt is 4 2.5p 1 2 3. As always in odd-period patterns, the 2.5p implies that one passer goes straight and one goes cross, 2.5p being a floaty flat (aka “zap” or “joe pass”).

The next step is to construct a manipulation pattern. We start from a solo pattern of period 5 with a 4 in it.

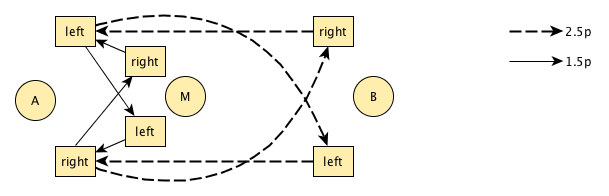

Number one on that list is 0 1 2 3 4. If we transform the 4 into a pass, we get 0 1 2 3 1.5p. It looks like this, again, with one passer doing straight and the other cross passes:

When we overlay the two patterns, we end up with:

| A: | 3 | 1.5p | 2.5p | 1 | 2 | |||||

| M: | 2 | 3 | 1.5p | 0 | 1 | |||||

| B: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2.5p |

The passers have to agree on who passes the 2.5p straight and who passes it cross. For the 1.5p, the manipulator can dodge the flat passes between A and B best if she smashes the 1.5p straight, while the passer doing the overlay smashes the 1.5p cross. Note that in contrast to conventional takeouts the passer, too, has a smash-in.

We call this combination Mission Impossible, partly because it was surprisingly difficult to get your head around the overlay part (A), partly out of reverence for Lalo Shifrin’s famous movie theme - one of the few widely known songs in a 5/4 time signature. Try chanting along with the rhythm!

Once you have this pattern solid you can move on to the Impossible Roundabout, a matter for a second article. As a preview we can already outline the most important and difficult aspect, which is to be clear about what is cross and what is straight. There are some intricacies about starting, permutations and a peculiar role swapping irregularity - but we will cover these in a follow up post.

Observations, Discussion

What we find most remarkable about this set of patterns is how hard it is to get one’s head around the overlay role (passer A). Even though in both examples all the two-person passing parts are fairly easy, it takes quite some time to manage both patterns at once. Naturally, this applies especially to odd period patterns, where you have to learn the pattern once for the first half and another time when you switch hands.

However, and this is true for many takeouts and (mini) Prechac patterns - once you master the timing around the difficult throws like the 4s and you don’t have to think actively any more, you can get the pattern solid relatively quickly. And doing the pattern solidly then suddenly feels like being part of a clock work on the one hand and watching it with a detached kind of admiration at the same time on the other hand. This mix probably accounts for a significant amount of the attraction of juggling takeout patterns.

The second observation worth noting is that the passers are aware of the manipulation, much in contrast to conventional takeouts where the manipulation is supposed to be transparent to the passers, in that the passers do not notice it.

In our view this is not problematic, since in reality the passers are always aware of the manipulation - an intercepted self is sometimes even called a ‘pelf’ to indicate that it is thrown gently (like a light pass) towards the manipulator. In contrast, our approach explicitly spells out the interaction between manipulator and passer, rather than assuming that it is transparent to the latter.

Future Work

We have various future plans to cover more of this family of patterns.

First of all we need a more solid description of the run around version of Mission Impossible. To do that, a closer comparison of these patterns with Aidan’s and Ed’s framework should help. We might be able to describe the run around aspect elegantly with that notation. Taking this idea further, it would be nice to have a general theory to turn our set of patterns into runarounds, which could possibly be as easy as confirming that Ed’s notation can be applied in general.

The more practical way ahead is obviously to generate more interesting patterns, especially with slightly more clubs to eliminate situations where we could actually stop the pattern with two clubs for each person. Examples of that could be a manipulated versions of “Why Not”, “Not Why” or “Why the heck”.